|

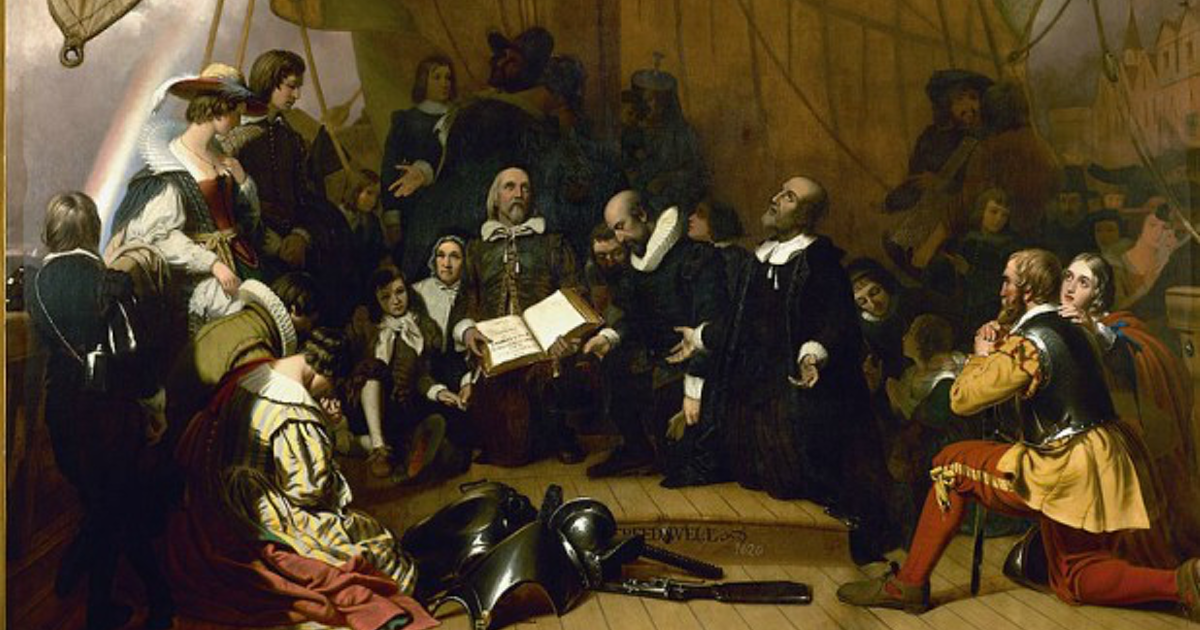

By Thomas DiLorenzo [Editor's Note: The following is excerpted from Thomas DiLorenzo's book The Problem with Socialism] The first American settlers originally adopted communal or socialized ownership of land and property. As a result, most of them rather quickly starved to death or died of disease. When the first pilgrims arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, in May 1607 they found incredibly fertile soil and plentiful seafood, wild game, and fruits of all kinds. Despite all of this, within six months all but thirty-eight of the original 104 Jamestown settlers were dead, having starved.(1) Two years later, 500 more pilgrims arrived in Virginia, transported there by the Virginia Company, and a shocking 440 of them died from starvation or disease. This became known as “the starving time,” described by one eye witness: “So great was our famine, that a savage we slew and buried, the poorer sorte took him up againe and eat him; and so did divers one another boyled and stewed with roots and herbs.”(2) This man also remarked that the cause of the starvation was “want of providence” and “industrie” and “not the barenness and defect of the Countrie, as is generally supposed.”(3) In other words, the problem was lack of effort, not a lack of resources.” The essential problem was that all of the pilgrims were indentured servants who had no financial stake in the fruits of their own labor. All that they produced went into a common pool to be used to generate profits for the Virginia Company as compensation for transporting them to America, and to support the colony. Working harder, longer, or smarter produced no additional benefit to anyone because the system that was set up was essentially agricultural socialism and everyone was compensated the same regardless of individual effort. The absence of property rights in the land, and of any link between effort and reward, destroyed the work ethic of the pilgrims, just as it always does in any socialist society, whether that of the Jamestown pilgrims or that of the former Soviet Union. Historian Philip A. Bruce wrote of the Jamestown pilgrims that the men idled over their tasks or refused to work altogether, and men who were known to be young and energetic by nature were “derelict.”(4) In 1611 the British government sent Sir Thomas Dale to serve as the “high marshal” of the Virginia colony. Dale noted that the surviving settlers were healthy and spent much of their time playing games and other vigorous activities. He immediately identified the source of the colony’s problem as the system of socialized land ownership. Consequently, he determined that each man would be given three acres of private land from which he was only required to pay a tax of two-and-a-half barrels of corn to the Virginia Company. Everything else was his to keep or sell. The Jamestown pilgrims then began to prosper. Each man realized that by loafing or shirking, he was paying the full cost of such behavior in the form of lost profits. At the same time, everyone realized that increased effort led to increased rewards. As historian Matthew Page Andrews wrote, “As soon as the settlers were thrown upon their own resources, and each freeman had acquired the right of owning property, the colonists quickly developed what became the distinguishing characteristic of Americans—an aptitude for all kinds of craftsmanship coupled with an innate genius for experimentation and invention.”(5) The private property system that replaced agricultural socialism in the Jamestown colony was quickly expanded so that each settler who paid his own way was given fifty acres of land, and by 1623 all land had been converted to private ownership. Capitalism replaced socialism and the pilgrims thrived. The same tragic mistake of adopting agricultural socialism was made in the Massachusetts colony where about half of the original pilgrims who landed in Cape Cod in 1620 were dead within a few months. Fortunately, the leader of the Mayflower expedition, William Bradford, recognized the problem: “For the young men that were most able and fit for labour and service, did repine that they should spend their time and strength to work for other men’s wives and children without any recompense. The strong, or man of parts, had no more division of victuals and clothes than he that was weak and not able to do a quarter the other could; this was thought injustice. . . . And for men’s wives to be commanded to do service for other men, as dressing their meat, washing their clothes, etc., they deemed it a kind of slavery, neither could many husbands brook it. (6) Socialism was the root cause of the starving pilgrims in the original Massachusetts colony. Bradford recognized this and, like his Virginia predecessors, decided to abandon agricultural socialism and allow private property ownership. In his own words, it was decided that the pilgrims of Massachusetts . . . should set corn for every man for his own particular, and in that regard trust to themselves; in all other things to go on in the general way as before. And so assigned to every family a parcel of land, for present use . . . and ranged all boys and youth under some family. This had very good success, for it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corn was planted. . . . The women now went willingly into the field, and took their little ones with them to set corn; which before would allege weakness and inability. . . .(7) By 1650 privately owned farms were as predominant in Massachusetts as they were in Virginia and elsewhere in the colonies, and the American economy began to thrive and prosper. The institutions of private property and free markets led to a burst of entrepreneurship and wealth creation. By 1776 the young American economy was a hundred times larger than it was in the 1630s, and Americans had already become among the most affluent people in the world. (8) (1.) George Percy’s Account of the Voyage to Virginia and the Colony’s First Days,” in The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1606-1689, Warren M. Billings, ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1975), 22–26.

(2.) Ibid., 28. (3.) Ibid. (4.) Philip A. Bruce, Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century (New York: Macmillan, 1907), 212. (5.) Matthew Page Andrews, Virginia, The Old Dominion, vol. 1 (Richmond: Dietz Press, 1949), 59.” (6.) William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620–1647 (New York: Knopf, 2002), 116. (7.) Ibid., 120. (8.) Jeremy Atak and Peter Passell, A New Economic View of American History (New York: Norton, 1994), 50. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed