|

By Lawrence W. Reed

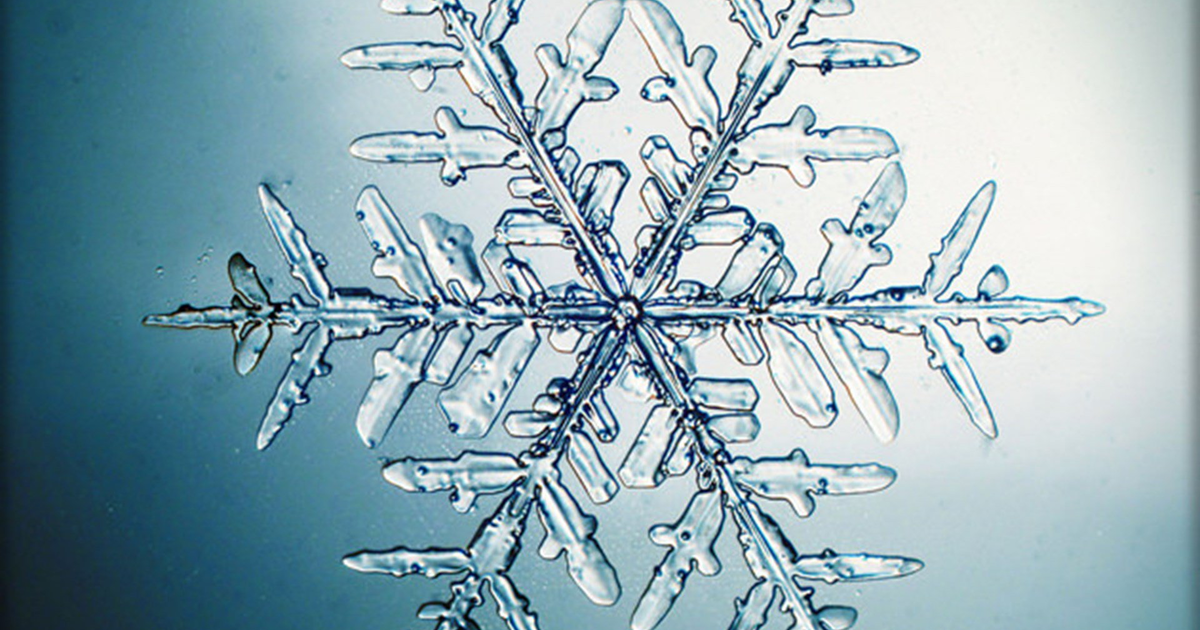

There are two basic prisms through which we can see, study, and prescribe for human society: individualism and collectivism. These worldviews are as different as night and day, and they create a great divide in the social sciences. That’s because the perspective from which you see the world will set your thinking down one intellectual path or another. No Two Alike I think of it as the difference between snowstorms and snowflakes. A collectivist sees humanity as a snowstorm, and that’s as up-close as he gets if he’s consistent. An individualist sees the storm, too, but is immediately drawn to the uniqueness of each snowflake that composes it. The distinction is fraught with profound implications. No two snowstorms are alike, but a far more amazing fact is that no two snowflakes are identical either — at least so far as painstaking research has indicated. Wilson Alwyn Bentley of Jericho, Vermont, one of the first known snowflake photographers, developed a process in 1885 for capturing them on black velvet before they melted. He snapped pictures of about 5,000 of them and never found two that were the same — nor has anyone else ever since. Scientists believe that changes in humidity, temperature, and other conditions extant as flakes form and fall make it highly unlikely that any one flake has ever been precisely duplicated. (Ironically, Bentley died of pneumonia in 1931 after walking six miles in a blizzard. Lesson: One flake may be harmless, but a lot of them can be deadly). Contemplate this long enough and you may never see a snowstorm (or humanity) the same way again. Dr. Anne Bradley is Vice President of Economic Initiatives at the Institute for Faith, Work and Economics. At a recent FEE seminar in Naples, Florida, she explained matters this way: When we look at a snowstorm from a distance, it looks like indistinguishable white dots peppering the sky, one blending into the next. When we get an up-close glimpse, we see how intricate, beautiful, and dissimilar each and every snowflake is. This is helpful when thinking about humans. From a distance, a large crowd of people might look the same, and it’s true that we possess many similar characteristics. But we know that a more focused inspection brings us nearer to the true nature of what we’re looking at. It reveals that each of us bears a unique set of skills, talents, ambitions, traits, and propensities unmatched anywhere on the planet.

This uniqueness is critical when we make policy decisions and offer prescriptions for society as a whole; for even though we each look the same in certain respects, we are actually so different, one to the next, that our sameness can only be a secondary consideration.

Primary Uniqueness The late Roger J. Williams, author of You Are Extra-Ordinary and Free and Unequal: The Biological Basis of Individual Liberty (as well as several articles in The Freeman), was a noted biochemistry professor at the University of Texas in Austin. He argued that fingerprints are but one of endless biological characteristics unique to each of us, including the contours and operation of our brains, nerve receptors, and circulatory systems. These facts offer a biological basis for the many other differences between one person and the next. Einstein, he noted, was an extremely precocious student of mathematics, but he learned language so slowly that his parents were concerned about his learning to talk. Williams summed it up well more than 40 years ago when he observed, “Our individuality is as inescapable as our humanity. If we are to plan for people, we must plan for individuals, because that’s the only kind of people there are.” Proceeding one step further, we must recognize that only individuals plan. When collectives are said to “plan” (e.g., “The nation plans to go to war”), it always reduces to certain specific, identifiable individuals making plans for other individuals. The only good answer to the collectivist question, “What does America eat for breakfast?” is this: “Nothing. However, about 315 million individual Americans often eat breakfast. Many of them sometimes skip it, and on any given day, there are 315 million distinct answers to this question.” Collectivist thinking is simply not very deep or thorough. Collectivists see the world the way Mr. Magoo did — as one big blur. But unlike Mr. Magoo, they’re not funny. They homogenize people in a communal blender, sacrificing the discrete features that make us who we are. The collectivist “it takes a village” mentality assigns thoughts and opinions to amorphous groups, when, in fact, only particular people hold thoughts and opinions. Read the rest of this article at the Foundation for Economic Education. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed