|

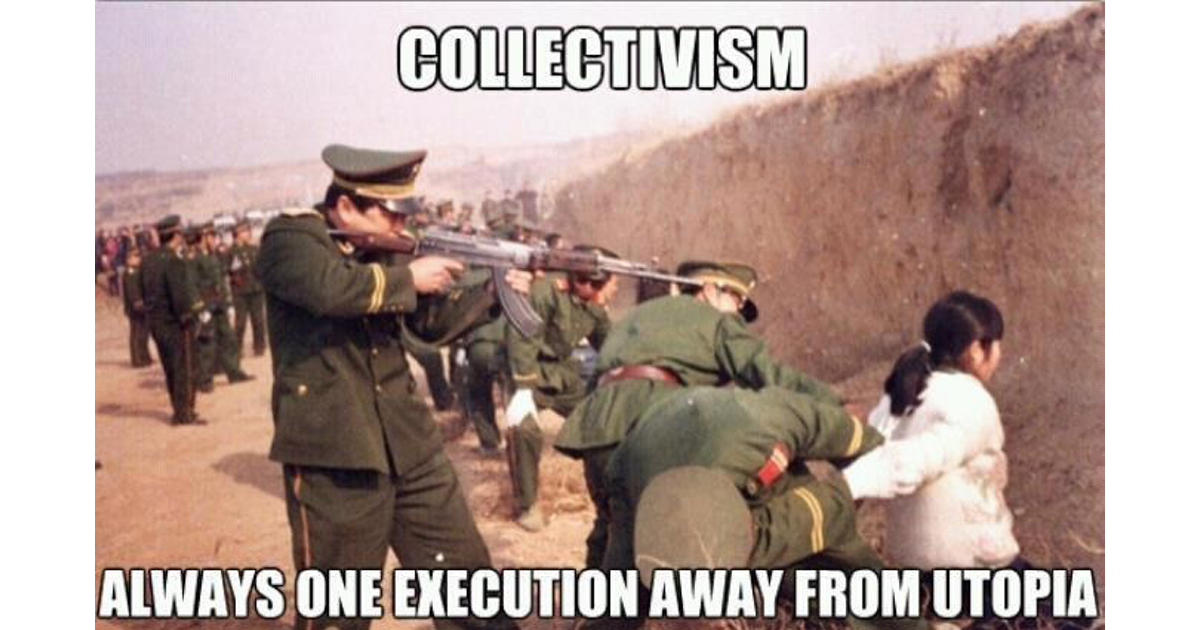

By Jeff Thomas Recently, I penned an article entitled “A Chicken in Every Pot,” which described the reasons why countries that have delved into collectivism are likely to slide further down the slippery slope once its addictive qualities have been introduced to the brain. Since then, I’ve received requests to address whether it’s ever possible to fully escape collectivism once it has taken hold in a country. The short answer is “yes.” It’s always possible to kick an addiction, but it’s not easy nor without pain. There are two forms of exit from collectivism. The first is national; the second is personal. Ending Collectivism Nationally Russia has crawled out of the collectivist tar pit, but not before an economic collapse in 1991. The political leaders that were responsible for the reinforcement of collectivism were able to bail out and retire in comfort to their dachas, whilst the hoi polloi suffered the pain of collapse and slow recovery. East Germany made a concurrent recovery from collectivism but had a bit of help from the more free-market West Germany after their reunification. (This fast-track form of recovery is rare.) The German recovery is especially notable, as the West Germans eagerly encouraged the East Germans to join the job market and otherwise participate in the then-vibrant West German economy. The initial result was that, whilst East Germans looked forward to the opportunity to have more money, better jobs, bigger apartments, and luxuries like new cars and televisions, they began whingeing immediately at the longer hours and increased productivity expected by West German employers. They were also miffed at the loss of holidays, extended paid leave, medical benefits, and other unrealistic collectivist perks that West Germans did not receive. However, most Germans were of the same race and ancestry, so the East Germans could not cry, “discrimination.” As a result, they got on with the changes. However, the change in mindset was slow and, to this day, some older East Germans still grumble that they had hoped to gain free-market advantages whilst hanging on to collectivist perks. But, again, this is an anomaly. Generally, for an entire culture to rid itself of the addiction to collectivism, collectivism itself must play out. As Maggie Thatcher said, “the trouble with socialism is that, eventually, you run out of other people’s money.” Collectivism can hang on for decades, bleeding what remains of the free market in a given country, but eventually, it’s left with a bloodless corpse. At that point, the government can no longer deliver on its “entitlements,” because collectivism is not a productive system—it is a parasitic system. In most cases, in collectivism, like alcoholism, the country must bottom out before the realization sinks in that the addiction simply doesn’t work. A textbook case can be seen in Cuba, where the system was slowly bled dry by collectivism, and the Cuban people remained at the bottom of the prosperity curve for many years before they took action. Although the government remained staunchly collectivist, the people slowly created a black market, providing goods and services to tourists. Over time, thousands of people operated small restaurants and offered their houses for rent illegally to tourists. It’s important to note that the government did not change its view of what sort of system they wanted. On the contrary, they determinedly stuck to oppression until the black market was so rampant that it could no longer be controlled. The government then did what all governments do to what they cannot control: tax it. New laws were passed to provide the cuentapropistas the right to operate restaurants, guest houses, and taxis, but they now had to pay a fee to the government to do so. Over time, the number of cuentapropista private businesses swelled, and so did the government coffers. At this point in time in Cuba, the government is engaged in a wrestling match with itself. It’s resisting the passage of greater freedoms in order to maintain maximum control whilst at the same time legislating greater freedom to create a free market that will provide the government with greater revenue. (After all, the Castro concept is still officially the policy, but each bureaucrat wants to get rid of his rusty old Russian Lada and get a shiny new Hyundai, paid for by the cuentapropista revenue.) Although the world at large does not realise that this change is taking place, it’s truly a non-violent revolution that’s being generated by a people who had nothing left to lose. Collectivism had not only failed but bottomed. Most Cubans now understand that prosperity is created by working harder and being more inventive. A free-market Cuba is now in the making and at this point is unstoppable. Within ten years, the new Cuba will have fully blossomed and be highly productive (if it isn’t swallowed up by a larger and more powerful country that’s still working towards greater collectivism). Of course, the reader may well say to himself that he’s not especially eager to wait two generations or more to regain his freedom. He may seek to regain it soon. The good news is that this is possible, but he’d be naïve to think that he may do so by writing letters to his congressman, refusing to pay his taxes, or holding a placard at a protest demonstration. If he’s a citizen of the EU, US, UK, Canada, or other country that’s rolling ponderously toward collectivism, he’d be very foolish to believe that, if he were to stand in front of the government bulldozer, it might magically stop and reverse itself. It’s far more likely that his act would result in his own demise (either economic or physical). Ending Collectivism Individually But it’s entirely possible to end collectivism individually. The downside is that it cannot be done by remaining in a country where the central government (regardless of which party currently holds office) is charging headlong into collectivism. The solution is to step away from the bulldozer—to seek out jurisdictions where the government isn’t on the path to collectivism. Of course, as stated above, this doesn’t come without pain. Most people don’t especially wish to give up their houses, their neighbourhood, their job, and their friends and begin a life anew. It’s particularly difficult to move away from family members—grandparents, grown children, etc. Of course, it’s also true that the grandparents can be brought along to the new country if they wish to go. And, even if the grown children are shortsighted enough to believe that their home country will not further deteriorate, they might be very grateful in a few years if their parents had exited, thus paving the way for them when they belatedly realise that the writing is on the wall. Another one of the most common reasons for not effecting an escape from growing collectivism is that “it can be a fair bit worse before I’ll be really desperate. I’ll just wait until then.” Unfortunately, whilst it’s often relatively easy to escape a jurisdiction that isn’t fully collectivist, those who wait until the door has been shut find that they’ve waited too long. And if we observe the litany of new laws in the above-mentioned jurisdictions, there can be no doubt that ownership of bank deposits has ended, assurance that continued possession of nonfinancial assets has been lost, and freedoms of speech and international travel are presently under fire. At present, third-world immigrants are noisily coming into the above jurisdictions in large numbers. Meanwhile, smaller numbers of those who are educated, skilled, and productive are very quietly leaving those same jurisdictions. To be sure, this is a challenge. It takes forethought, planning, and commitment. But the reward is the greater likelihood of a rebirth into a new home where opportunity and freedom still thrive. There are quite a few such destinations out there, but the first step must be to decide to make the move. This article was originally published at International Man.

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed