|

By Jacob Hornberger

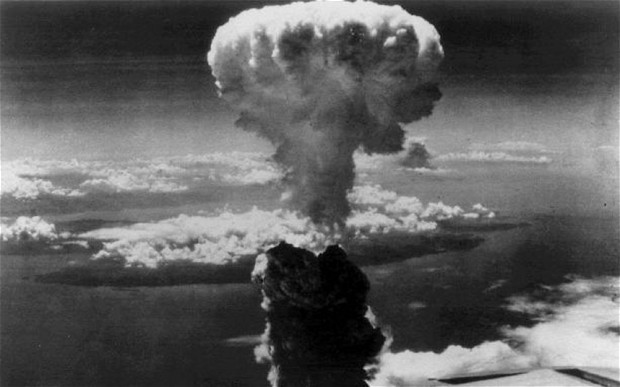

I don’t get it. On the one hand, we’re told that the intentional targeting of civilians in wartime is a war crime. On the other hand, we’re told that the intentional targeting of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear bombs was not a war crime. Which is it? The issue is back in the news with President Obama’s decision to visit Hiroshima. The question that is being debated is whether he should apologize for President Truman’s decision to order U.S. troops to drop nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. If the targeting of civilians in wartime is okay, then clearly the decision to nuke the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not a war crime. But if that’s the case, then why was U.S. Army Lt. William Calley prosecuted during the Vietnam War? He’s the officer who intentionally killed several defenseless women and children in a Vietnamese village. The military prosecuted and convicted him of a war crime. Why? If it’s not a war crime to intentionally kill women and children in wartime, then why was Calley prosecuted and convicted of war crimes? The fact is that it is a war crime for troops to intentionally target non-combatants in wartime. Nobody disputes that. But then given such, why the pass on Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Everyone agrees that Truman was targeting non-combatants — mainly women, children, and seniors — when he ordered the nuking of those two cities. How do defenders of Truman’s decision avoid the inexorable conclusion that Truman’s action constituted a war crime? Their primary argument is that the nuclear bombings of the cities shortened the war, thereby saving the lives of thousands of U.S. soldiers who would have died had the war been continued to be waged, especially if an invasion of Japan had been necessary. That’s in fact the rationale that has been cited for decades by U.S. soldiers who were fighting the Japanese in the Pacific. Many of them have expressed gratitude over the years for what Truman did because it enabled them to live the rest of their natural lives while, otherwise, they might have been killed in subsequent battles. But there are big problems with that rationale. For one, the fact that killing non-combatants might or will shorten a war is not a legal defense to the war crime. Suppose Calley had said that his killing of those women and children had shortened the Vietnam War or that he intended to shorten the war by his actions. Would that have constituted a legal defense at his war crimes trial? Or suppose U.S. airmen who have bombed all those wedding parties in Afghanistan were to say, “We did it on purpose because we felt it would shorten the war.” Would they be let off the hook at their war crimes trial? The answer is: No because that is not a legal defense to the war crime. The law does not say that the crime is excused if it succeeds in shortening the war or if it is intended to shorten the war. Moreover, once that rationale is accepted, then doesn’t it logically apply to both sides in a war? What’s to prevent an enemy nation from intentionally targeting American non-combatants during war under the rationale that by doing so, it is bringing the war to an early conclusion, thereby saving the lives of many of its soldiers? Once both sides are relying on that rationale, doesn’t that effectively nullify the legal prohibition? The fact is that soldiers die in war. That’s the nature of war. What’s one to say about a soldier who exclaims, “Thank you for killing those defenseless women, children, and seniors so that I could live out my natural life”? It’s certainly difficult to imagine Gen. George Patton ever saying such a thing. One cannot imagine that Patton would ever have been willing to kill defenseless women, children, and seniors if it meant that the lives of his soldiers would be spared. I think Patton would have said, “Get out there and fight. If you die, so be it. We are not going to kill defenseless women, children, and seniors just so you can live a longer life.” Some defenders of the nuclear attacks say that since Japan started the war, the Japanese people at Hiroshima and Nagasaki had it coming to them. But since when do individual citizens have much say as to when their nation goes to war or not? How much say did the American people have in George W. Bush’s and the U.S. national-security state’s decision to go to war against Iraq and Afghanistan? And let’s not forget who intentionally maneuvered, postured, and provoked Japan into attacking the United States, especially with his oil embargo on Japan, his freezing of Japanese bank accounts, and his settlement terms that were deliberately humiliating to Japanese officials. That would be none other than President Franklin Roosevelt, who was willing to sacrifice the soldiers at Pearl Harbor and in the Philippines in order to circumvent widespread opposition among the American people to getting involved in World War II. Isn’t there something unsavory about provoking a nation into starting a war and then using that nation’s starting the war to justify nuking its citizens in an attempt to bring the war to a quicker conclusion? Wouldn’t it have been better and less destructive to not have provoked Japan into attacking the United States in the first place? Defenders of the nuclear attacks also say that Truman had only two choices: nuking Hiroshima and Nagasaki and continuing the war until Japan surrendered. But that’s just not true. There was another option open to Truman — a negotiated surrender. Given Truman’s steadfast insistence, however, on “unconditional surrender” —a ludicrous and destructive position if there ever was one — a negotiated surrender was an option that he refused to explore, choosing instead to kill hundreds of thousands of non-combatants in order to secure his “unconditional surrender” from Japan, which, by the way, turned out to not be “unconditional” after all since Japan was permitted to keep its emperor as part of its surrender. The real reason why so many Americans still cannot bring themselves to acknowledge that the nuclear attacks on the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were war crimes is their inability or unwillingness to acknowledge that their own government, including their own president and their own military, were capable of committing and actually did commit a grave war crime–the intentional killing of noncombatants consisting primarily of women, children, and seniors. In the minds of many Americans, that’s something only foreign governments are capable of and willing to do, not their own government. This article was originally published at The Future of Freedom Foundation. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed